Dealing with Stock Market Declines

(Original post 10-27-18)

(Original post 10-27-18)

Stock market declines are a dime a dozen.

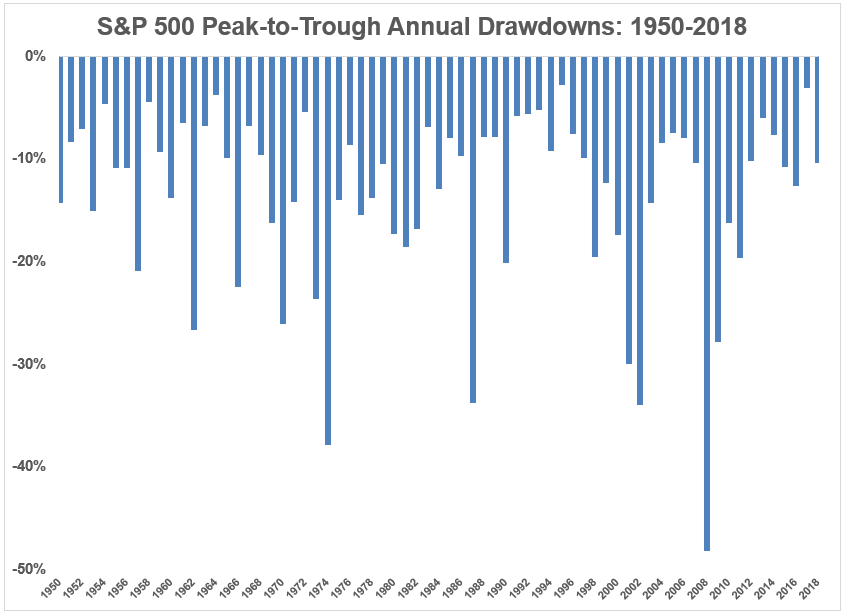

Over the course of any year, there's likely to be one or two 10% to 19% declines, commonly called “corrections.” Every few years, there’s likely to be a 20% decline—the common definition of a “bear

market.” Several times in your investing lifetime there will be a 30%,

40%, or 50% decline. Those are called “crashes” or “collapses.”

Think of all these events as "sales." The stock market is the only place where people run out of the store when there's a sale. Here's a great chart that shows how often and how big these sales are.

Think of all these events as "sales." The stock market is the only place where people run out of the store when there's a sale. Here's a great chart that shows how often and how big these sales are.

This is what markets do. And there’s a huge media enterprise that will tell you why it happens and “what to do next." All of it is hindsight-based and much of it contradictory; price always drives the media story line.

Here's something else: If you want to talk about abnormal, look at 2017! It had one of the lowest annual drawdowns ever! No wonder people got surprised when normality returned in 2018.

So, here's what you need to do now: Nothing! (Unless you've been waiting for a sale.)

Take a minute to recall what a real financial plan looks like.

One, whatever money

you think you might use in the next five years is kept behind a stock market firewall. It's in a checking account, savings account, bond funds, CDs, under a mattress, in a cookie jar. Return

is irrelevant. Safety and liquidity are primary. This is the Five-Year Rule.

This gives you the freedom to care less about what happens in

the stock market over any next five-year period because you always have the cash you need on hand. None of it hinges on what happens in the stock market. What a relief! You sleep well at night.

When stocks are rising, you’ll probably wonder why you have the Five-Year Rule. Ironically, that’s exactly when you need it most. Effective money management is highly counter-intuitive.

Next. You have an Asset Allocation Policy with 5% or 10% guardrails, yes? That policy was put in place after a deliberate, unemotional

assessment of your long-term needs and willingness to endure volatility. If the guardrails are violated, you

re-balance back to the policy target.

That’s it. The Five-Year Rule and Asset Allocation. All

the rest is entertainment.

In summary, know that we usually take the other side of our client's inclinations. When clients are enthusiastic with glee, we tend to be tentative and careful. When they are worried and frightened, we tend to be increasingly enthusiastic and optimistic.

Rising prices eventually bring risk and overvaluation; falling prices bring opportunity and set the stage for long-term profits. Of course, we accept good markets for what they are, but welcome with open wallets the seemingly less favorable.

An Even Bigger Picture

There's a wonderful set of graphics on stock market returns over long periods here.

You might want to also go back and read the October 17th post below on Re-Thinking Risk.

In summary, know that we usually take the other side of our client's inclinations. When clients are enthusiastic with glee, we tend to be tentative and careful. When they are worried and frightened, we tend to be increasingly enthusiastic and optimistic.

Rising prices eventually bring risk and overvaluation; falling prices bring opportunity and set the stage for long-term profits. Of course, we accept good markets for what they are, but welcome with open wallets the seemingly less favorable.

An Even Bigger Picture

There's a wonderful set of graphics on stock market returns over long periods here.

You might want to also go back and read the October 17th post below on Re-Thinking Risk.