Re-Thinking Risk

Most people tend to think of risk as sharp, dramatic downward movements of prices. That's why financial markets are viewed as risky. So, what are sharp, dramatic upward movements of prices? Is that risk?

They are both risks, but not in the simplistic way most people view them.

In his book Deep Risk, Bill Bernstein describes two different types of risks in financial markets:

One is "shallow risk,” a temporary loss of capital that is recovered fairly quickly,

say within several years; and “deep risk,” a permanent loss of capital.

Put differently, shallow

risk, if handled properly, deprives you only of sleep for a while; deep

risk deprives you of sustenance.

That said, people who decided to "be more conservative" in the wake of those events succeeded in converting shallow risk to deep risk-- they sold at a loss and converted shallow risk to deep risk-- the permanent loss of capital.

Perhaps surprisingly, bond bear markets are actually of the deep risk variety. They don't even show up on your account statements. They're the ones that slowly drain purchasing power and compromise your standard of living. It's the erosive grind of inflation; death by a thousand cuts.

That's why it's so important to understand household cash flow needs when making asset allocation decisions. You want to be in the position of ignoring shallow risk while guarding against permanent deep risk. Bernstein again:

Capital intended for near-term

needs should be guided by shallow risk, while capital managed for long-term needs should be guided by deep risk.

A default for this is to keep any capital likely to be used in the next five years behind a stock market firewall. Leave it in a checking account, savings account, CDs, bond funds, under the mattress. For the rest, you want to be most mindful of deep risk.

Inspiration for this post came from Ben Carlson's Worst Kind of Bear Market.

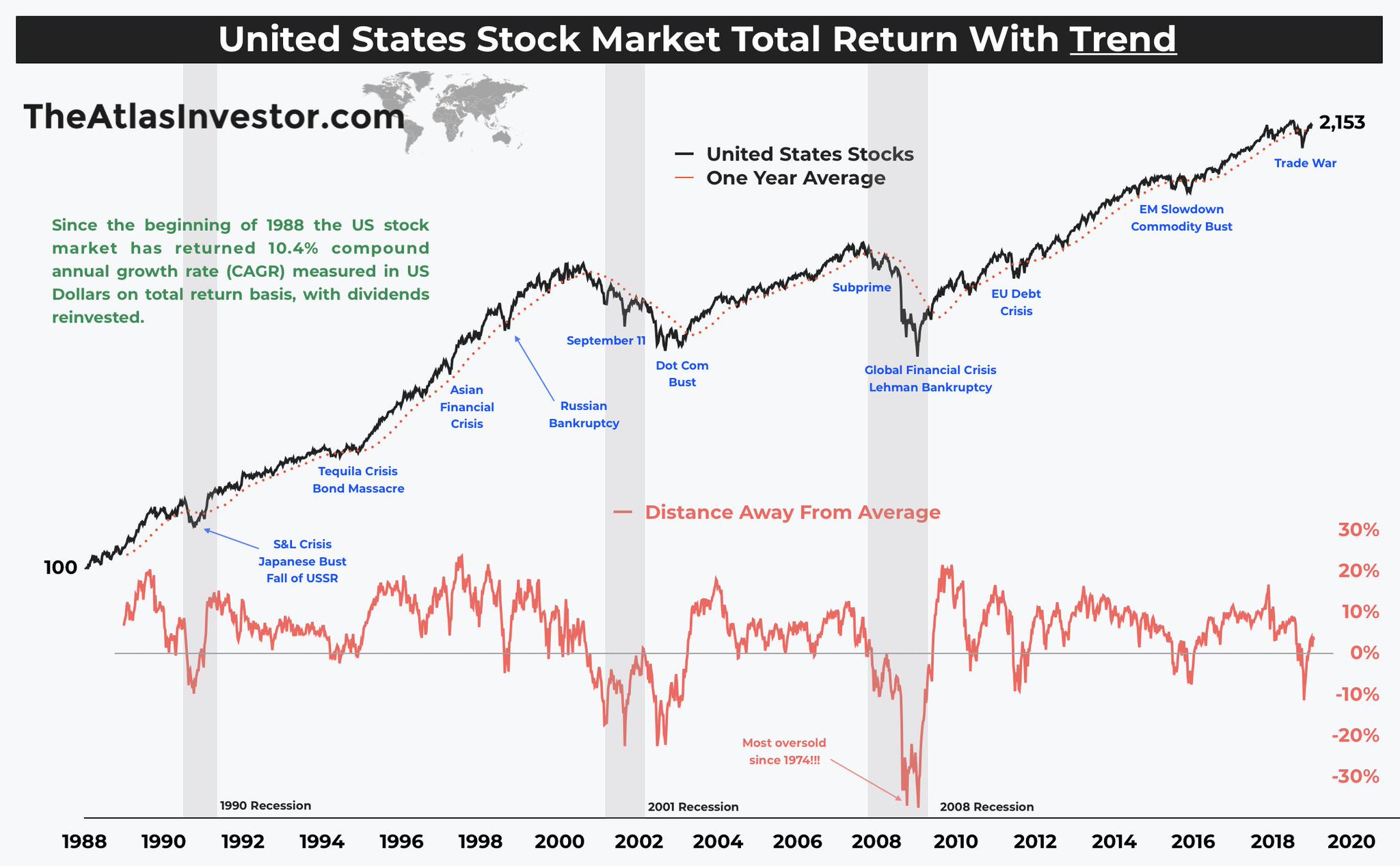

Another way of looking at risk is offered here. The chart in red is a mean-reverting representation of how

over or under extended prices might be. None of this is rocket science precision.